Ballistic Technology

Ballistic Technology

There are a number of ways to provide efficient protection against the impact of high velocity small arms bullets. Armours are commonly made of monolithic metals, fibre reinforced composite materials and ceramic faced metals or composites. An alternative approach is to use air gaps to make a spaced (or, as it is often called, split) armour system. In civil engineering structures, where the total thickness of protection may not be important, thin sheets of metal can be used to aid effective ballistic protection.

Thin metal sheets can also be positioned obliquely to the direction of impact in order to disrupt a small arms bullet by inducing yaw and, in some cases, by breaking the bullet. A monolithic or spaced armour positioned behind the front thin sheet of metal is then impacted by a less penetrative projectile. Multiple thin oblique sheets are also used in certain instances.

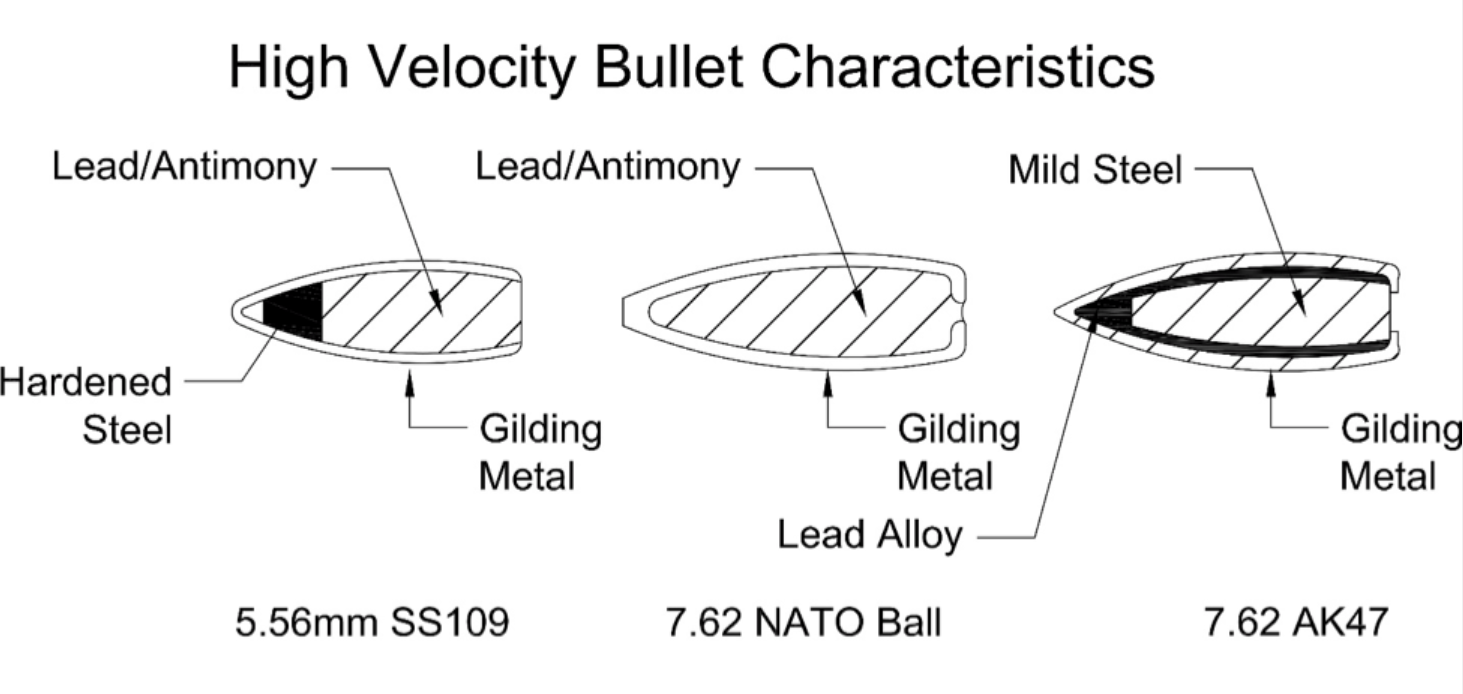

These are typical (called Ball) bullets used in military assault rifles. The 5.56mm calibre NATO (SS109, M855) bullet weighs 4g. Within its gilding metal jacket, the bullet contains a hardened steel tip weighing 0.4g in front of a lead/antimony core. With a muzzle velocity of up to 950m/s this bullet has similar penetrability to the 7.62mm calibre NATO Ball bullet which has a muzzle velocity of about 830m/s. This latter bullet, which weighs about 9.4g, contains a lead/antimony core encapsulated within a gilding metal jacket. The 7.62mm calibre M1943 bullet associated with the Kalashnikov AK47 rifle weighs 8g and has a typical muzzle velocity of 710m/s with, as a consequence, lower penetrability than the other two bullets. Within its gilding metal jacket it typically contains a mild steel penetrator weighing 3.5g encapsulated in a lead core (though there are many variations in this type of bullet).

The need for expedient protection against fragments and small arms fire is present in many military operations. Sandbags have long been used for such purposes but they are easily damaged with consequent loss of material and protective ability against multiple hits. Likewise, concrete and brickwork in buildings has good resistance to single hits with a loss of effectiveness against burst fire and multiple hits as material is lost by spalling and scabbing from the front and back faces. Adequate sandwiching of naturally occurring soils, selected aggregates and concrete to prevent material loss can increase the effectiveness of these systems for ballistic protection.

Plain Concrete

Plain concrete can offer effective ballistic protection if weight is not an important parameter. A ballistic impact, however, causes a crater around the point of impact and, unless the thickness of the concrete slab is sufficient, a second crater on the back face of the slab because of the effects of stress wave reflections. These scabbing and spalling phenomena do, however, reduce the resistance of the slab to subsequent impacts in their vicinity. As a consequence, the effectiveness of concrete against multiple hits is significantly compromised

When concrete is impacted by a projectile, such as a small arms bullet, there is damage and loss of material around the impact site (a front face spall crater). The bullet then forms a tunnel in the concrete. The compressive stress wave, which emanates from the point of impact, reflects from the rear face of a slab of concrete as a tensile wave. This produces a rear face scab crater unless the slab is sufficiently thick. The concrete is perforated when the tunnel joins the front and rear face craters to make a hole through the slab. In addition to the localised cratering and penetration, the concrete may suffer more extensive cracking radiating from and surrounding the impact area. The failure accumulates with successive impacts and perforation of the concrete occurs after a number of impacts. The resistance to multiple hits can be increased by supporting (i.e. containing) the concrete around its periphery. Total failure as a consequence of gross cracking can be prevented by lateral containment. Front and rear 'sandwich' containment of concrete gives excellent resistance to multiple hits. In a wall, concrete is under compressive loading in the vertical direction (the stresses are, however, small). This 'confinement' exists also in pre-stressed concrete structures and could be contemplated for some protective structures if it were beneficial to do so.

Larger calibre ammunition types

The M33 Ball bullet contains a sharp ogive nosed mild steel core tipped by lead/antimony within a gilding metal jacket. The Armour Piercing Incendiary (API) bullet is geometrically similar but the core is made of hardened steel and the lead/antimony tip is replaced by an incendiary composition. The Armour Piercing Incendiary Hard Core (APIHC) bullet contains, within a gilding metal envelope, an incendiary fronted cylindrical tungsten/nickel alloy core inside an aluminium alloy sleeve. ‘SLAP’ rounds are special purpose rounds containing a hardened steel projectile with a sharp conical nose (15° included angle).

Glazing

The requirement for transparency means that few materials are available that can be considered for transparent armours. Applications for such armours include windows and other forms of structural glazing plus visors (and goggles) as part of a system for personal protection.

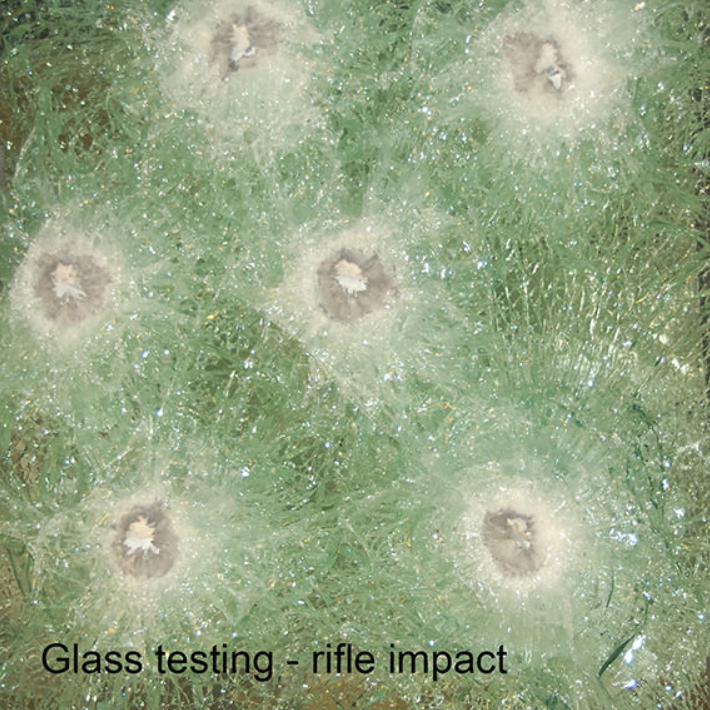

Glass is the best material for optical transmission and resistance to surface abrasion. Problems arise, however, because stress wave reflections cause glass to spall under ballistic impact. The resulting shards of glass that can be projected from its rear face may be almost as injurious as perforation by the impacting projectile itself. Somewhat tougher glass ceramics are being developed but most current transparent armours to give significant ballistic resistance use glass as a primary constituent.

Transparent plastics can provide protection against low levels of ballistic threat. Acrylics (i.e. polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) Perspex, Plexiglass) are good optically but, like glass, they are brittle. Polycarbonate (Makrolon, Lexan) has high impact strength but poor surface abrasion properties. Also, it is not very efficient at absorbing energy when the impact is localised - high kinetic energy density. It is best used against low energy density threats (e.g. for riot shields) and as a backing to acrylics or glass against high energy density threats to absorb energy and to contain back face spalling.

The back face spalling of a glass based system can be reduced by using toughened glass rear layers or backing layers of polyester film or polycarbonate.

In order to maximise the efficiency (i.e. minimise the weight) of transparent armour systems, complex laminates are common using poly-vinyl-butyrate and polyurethane adhesives to bond layers of glass and polycarbonate. Spaced systems are also used for some structural applications where bulk is not a major disadvantage.

Ballistic glass consists of a number of layers of glass bonded together with a plastic interlayer as can be seen here:

Frequently Asked Questions

What do you mean by “ballistic technology”?

At Blast & Ballistics, ballistic technology refers to the science and engineering of stopping bullets and fragments using the right combination of materials and construction. That includes monolithic metals, fibre-reinforced composites, ceramic-faced armours and spaced (split) armour systems, all designed to defeat specific small-arms and larger-calibre threats used in today’s rifles and machine guns.

How do you design an efficient ballistic protection system?

We look at the threat, available space, weight limits and structural constraints, then select the most efficient armour concept for the job. This may be a single metal plate, a multi-layer steel/composite/ceramic solution, or a spaced armour system using thin, sometimes oblique metal sheets to yaw or break the bullet before it hits the main armour. In civil structures, where thickness is less critical, we can also use contained concrete, soils or aggregates to provide robust multi-hit protection.

What types of ammunition do your designs take into account?

Our ballistic technology work covers a wide range of threats, from 5.56 mm and 7.62 mm NATO Ball bullets to common AK47 (7.62×39 mm) rounds, and larger-calibre ammunition such as .50 calibre Ball and armour-piercing (API, APIHC and SLAP) projectiles. Understanding the construction, mass and velocity of each bullet type allows us to design armour systems that give reliable, tested protection at the required level

How does Blast & Ballistics approach transparent armour and ballistic glazing?

Transparent armour is a key part of our ballistic technology. We engineer laminated glass and plastic systems that balance optical clarity, weight and ballistic performance. Glass offers excellent optical quality but tends to spall under impact, so we use multi-layer laminates with toughened glass, poly-vinyl-butyral / polyurethane interlayers and polycarbonate backing to catch spall and absorb energy. The result is ballistic glass and glazed screens that deliver certified protection while still looking like normal glazing.

Can you help upgrade existing buildings with better ballistic protection?

Yes. Our ballistic technology expertise is often used to improve existing structures. We can advise on how to use steel or GRP ballistic panels, contained concrete, sandwiched walls and transparent armour to upgrade walls, façades and internal partitions. By combining practical materials (e.g. concrete, aggregates, GRP) with engineered armours and glazing, we help clients achieve a tested level of ballistic protection without necessarily rebuilding from scratch